Tinsel in July: The Incarnational Power of (De)Tale

Daniel Bowman Jr. teaches English at my alma mater. One would think that this would be how we met, but it isn't. Instead, we connected through the marvelous, sometimes surprising ether of the Internet, long after the ink on my diploma was dry. I have found him to be a wonderful poet, writer and friend. I'm so pleased to share these words of his with you today. I think you'll find that they catch the light at just the right angle. ...

“Conversation between [the poet and the Christian theologian] is critical, for if the latter is to get to grips with the slippery shape of the incarnation, he must employ a medium which excels in the small glories of particularity.”

—Andrew Rumsey in Beholding the Glory: Incarnation through the Arts [1]

“…I’m running down baseballs in the backyard, searching through tinseled trees for a home run…”

—from “The New Literacy” in A Plum Tree in Leatherstocking Country [2]

Lately I’ve been traveling in the name of poetry. I had the pleasure of reading at the Sullivan Munce Cultural Center in Zionsville, Indiana, through the Poetry on Brick Street series. A few days later I read at Wheaton College outside of Chicago, then at the Hi-Spot Café in Seattle. Each time I read an older poem called “The New Literacy.”

It’s the first poem I ever published. I glowed when it came out in Seneca Review, mere pages from work by James Tate, whose Selected Poems—a book I loved—had won the Pulitzer. A senior English Ed major at Roberts Wesleyan College, I’d been stocking shelves at the Towne Plaza IGA the day my contributor’s copy arrived. The publication affirmed me, seemed a sign of better things to come, perhaps even a future built on literature. I had entered the “Great Conversation” of literature.

What I’ve been thinking about lately is not when I entered the conversation, but how.

When I introduce “The New Literacy,” I mention that the title refers to a new kind of seeing, going back to my beginnings as a poet. The poem is filled with images that obsessed me, specific details from the time and place where I grew up. When I began to think of myself as a poet, I realized that I was seeing the world around me differently, “reading” it as one simultaneously experiencing it and transforming it into art. So if the first literacy was learning to read as a child, then the second, or new, literacy was, for me, learning to see the world through the eyes of the artist.

That’s the poem’s contribution, its humble way of entering the conversation. Or so I had always thought.

* * *

I’ve been reflecting back on my recent poetry readings. And when I think of “The New Literacy,” I don’t think at all about seeing the world as a series of images. I think only about an image, one small detail from the poem, where the speaker says that he’s “running down baseballs/ in the backyard,/ searching through tinseled trees/ for a home run….”

I can still see those tinseled trees.

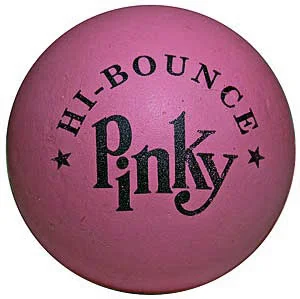

When we were growing up in New York’s Mohawk River Valley, my brother Billy and I played baseball all summer. We used a whiffle bat and a pink rubber ball known as a Spaldeen or Pinky. The ball had a lot of bounce in it, testing the limits of the hollow yellow plastic bat, which often required fortification via duct tape.

Our yard formed a natural if very tiny ballpark. The hill that framed the southern part of the yard made an ideal outfield wall. A base hit would often bounce off the wall, enabling the fielder to make a play on the ball. If the batter reached base safely, we used an intricate system of “shadow men” as base runners, allowing us to tally runs scored and RBI. (We took our baseball “league” seriously, and Billy kept meticulous hand-written records of all of our players and their statistics.)

If you hit the ball clear over the hill, it was, of course, a home run.

And since we never had more than one or two rubber balls at a time, it was the fielder’s job to climb the hill and search for the homerun ball while the batter trotted the base paths, celebrated, and notched his requisite markings in the scorebook.

Just over the hill and in the ravine sat a pile of our old Christmas trees. When the holidays were finished, we’d un-decorate the tree, and that’s where we’d toss it. Our baseballs had a way of rolling and bouncing along through the old Christmas trees and finally settling into crannies that made them difficult to retrieve. We’d almost always get the ball back, but it took some elaborate maneuvering.

Picking through the piney boughs, it wasn’t uncommon to see a stray strand of tinsel faded by the elements but retaining some original silver sheen. After all, it was tough to remove every last piece during the sad job of packing things up after Christmas.

Each time I spotted a silver tinsel strand in the sweaty heat of July, it immediately took me back to a different season, a different world: deep cold, enormous bluffs, sledding, colored lights, and coveted Christmas presents—including baseball cards.

* * *

I felt amazed at the confluence of winter and summer, cold death and verdant life. It amazes me still. It calls to mind—apropos of the Christmas season—the great paradoxes of faith. Christ whose birth we celebrate is both wholly God and wholly man; wholly Other and wholly us; his “yoke is easy and [his] burden is light,"[4] yet to follow him means to take up a cross—because in order to live, we must, in fact, die.

Part of taking up that cross, I think, is to grow a space inside where we can hold the difficult personal paradoxes together. For example, I know that in order to save my life, I must lose it; and in order to be first, I must be last. These are hard sayings that require fundamental shifts.

Toward the end of his life, as the Cold War dominated international headlines, Carl Jung was asked if he thought there would be an atomic war. According to Barbara Hannah, his reply was this:

“I think it depends on how many people can stand the tension of the opposites in themselves. If enough can do so, I think the situation will just hold, and we shall be able to creep around innumerable threats and thus avoid the worst catastrophe of all: the final clash of opposites in an atomic war.” [3]

For Jung, holding “the tension of opposites” within one’s self was a key to peace, to the wholeness of the individual and by extension the community and the world.

The stakes of paradox are high, and yet the ideas are abstract, hard to get ahold of. Perhaps this is why Andrew Rumsey speaks of the Christian theologian and the poet as needing one another. He says that if the theologian is “to get to grips with the slippery shape of the incarnation, he must employ a medium which excels in the small glories of particularity,” namely poetry.

Poetry helps us learn to live with the tensions, imaginatively inhabiting them through the tales we tell and the particular details we use in the telling—especially the details where we can see opposites quietly abiding together:

The baseball hiding beneath the old Christmas tree, a strand of tinsel flickering in the summer breeze.

The God-man who entered human history in a particular place and particular time and yet was present at the creation and will rule for all eternity.

In the end, the tensions of poetry, the paradoxes we find in the vivid and specific details are our lives, are nothing short of messy, beautiful incarnation, pointing the way toward peace and wholeness.

...

Daniel Bowman Jr. is the author A Plum Tree in Leatherstocking Country (VAC Poetry, 2012) and Beggars in Heaven: A Novel (Relief Books, fall 2014). A native of the Mohawk Valley in upstate New York, he lives with his wife, Bethany, and their two children in Hartford City, Indiana. He is Assistant Professor of English at Taylor University.

Daniel Bowman Jr. is the author A Plum Tree in Leatherstocking Country (VAC Poetry, 2012) and Beggars in Heaven: A Novel (Relief Books, fall 2014). A native of the Mohawk Valley in upstate New York, he lives with his wife, Bethany, and their two children in Hartford City, Indiana. He is Assistant Professor of English at Taylor University.

Find him on Twitter: @danielbowmanjr.

Bibliography

[1] Begbie, Jeremy, ed. (2000) Beholding the Glory: Incarnation through the Arts. Grand Rapids: Baker.

[2] Bowman Jr., Daniel. (2012) A Plum Tree in Leatherstocking Country. Chicago: Virtual Artists Collective.

[3] Mehrtens, Sue. (2013) Jung’s Challenge to Us: “Holding the Tension of Opposites”. Jungian Center for the Spiritual Sciences. http://jungiancenter.org. Retrieved 3-1-14.

[4] Matthew 11:30, New International Version.

...

You can check out the other de(tales) (so far) here.